|

Oct. 28, 2000 By Tom Vaughan

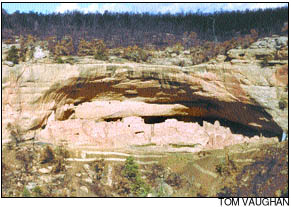

Officials at Mesa Verde National Park are using lessons learned from the August 1996 Chapin 5 Fire in their Bircher and Pony fire recovery programs. The Chapin 5 Fire burned 4,782 acres, the largest area a single fire had burned in Mesa Verde National Park up to that time. The Bircher Fire started July 22 on private land just east of the park and burned 23,600 acres. The Pony Fire began in the Ute Tribal Park west of the national park on Aug. 2 and burned 5,300 acres. All three fires were ignited by lightning strikes. During a media tour in the national park Wednesday, Chief of Research and Resources Management Linda Towle reported, "We are almost a year ahead of where we were on the Chapin 5 Fire in terms of getting treatment on the ground." The interim manager of the post-fire rehabilitation team, Jane Anderson, said the park would be "starting a big reseeding program" Thursday that would reseed 6,000 acres with native plants. She said the park staff learned after Chapin 5 that early reseeding with native species was effective both in encouraging ground cover to retard erosion and in preventing the invasion of exotics such as thistles. A dialogue on fire-rehabilitation aims and practices was also established with Indian tribes after the Chapin 5 Fire and has now been focused on the Bircher and Pony fires. Noting that consultation with tribes is a requirement of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, Anderson said the park regularly meets with representatives of 24 tribes connected with Mesa Verde. "We have a core group of consultants," she said, consisting of representatives of nine tribes designated by the consulting body at their annual meeting in September. "We’re following practices that we’ve already established in the Chapin 5 Fire," Anderson explained, and "they’re comfortable with that." She said no human remains have been found in the newly burned areas, though erosion in the spring may bare skeletal remains. The rehabilitation effort is trying to "triage what we can do this fall" before bad weather sets in, she said. One factor allowing quick response, she related, was the availability of labor through the Weeminuche Construction Authority, an enterprise of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. The park contracted with them through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Anderson said the current rehabilitation effort has received $3.4 million, of which $2.3 million went to the NPS, $40,000 to the BLM and $200,000 to BIA for work in the tribal park. When the media-tour group paused at the Long House overlook on Wetherill Mesa, local archaeologist Doug Bowman described the NPS/Ute cooperative effort in action. NPS archaeologists assessed the damage to Long House and made recommendations for emergency stabilization. When the Weeminuche workers entered the park to lay excelsior matting, stabilizing the surface of the soil and cutting off potential erosion channels, "it took one day to do the site." Bowman is a former superintendent of the Ute Tribal Park who is now serving as liaison with the NPS rehabilitation effort and directing the post-fire response within the tribal park. Bowman is excited about the scientific information the tribal park will potentially gain from the rehabilitation effort. In the Chapin 5 burn area, Anderson said 372 new sites were added to the 295 sites already known from previous surveys. Assuming site density in the tribal-park portion of Mesa Verde is comparable, Bowman predicted they might find 500 more sites in the relatively unsurveyed Pony Fire burn, where only 44 sites are known. Bowman said he will be going to foundations for grants to supplement the tribal park’s funding from the rehabilitation fund. "It’s a wonderful opportunity," he said, to increase knowledge of the Ute Tribal Park’s resources and he is optimistic about getting a good hearing. So far, according to Anderson, the team has assessed 80 ground (surface) sites and 50 alcove ("cliff-dwelling") sites, and about 50 sites have been treated. These numbers, which include both previously known and newly discovered sites, increase daily as the teams comb the burn areas. With regard to Step House, a popular cliff dwelling on Wetherill Mesa that has been open on a self-guided basis, the fire created several problems for future visitation. Will Morris, Mesa Verde public-affairs officer and chief of interpretation, pointed out that the fire burned a footbridge on the entrance trail, scorched the ladders in the ruin and bared the "steps" to the mesa top which gave the site its modern name. In addition, the sandstone alcove got so hot that plates of stone are continuing to spall off the roof, endangering anyone below. The stability of the sandstone will be a major safety factor in determining when, or if, visitors can return to Step House, Morris said. While most of the attention on the tour was given to the rehabilitation effort, the eerie, burned-out backdrop was a constant reminder of how much work lies ahead before visitors can return to Wetherill Mesa. Rainwater has already cut channels, carrying silt over roads and trails to a depth of three inches in some places. Sites and artifacts previously under oak brush are now naked in the scorched landscape, defenseless against the impact of thoughtless or acquisitive visitors. Except for the road, the only modern facilities left standing in the Wetherill Mesa developed area are the concrete shelters over the exposed surface sites. In one of those sites, a coating of windblown ash and soil already covers all of the excavated features. The skylights of the shelters now let water in as well as light, and the side curtains that kept out moisture in the form of snow have burned away. If the shelters cannot be weather-proofed before winter, Towle said, the earthen features inside will virtually melt away. The ARAMARK/Mesa Verde Company lunch stand and shelter at Wetherill is only a concrete pad with a partial roof. The ranger station is gone. The restrooms are obliterated. In short, there are no facilities left to support visitation. Rebuilding visitor facilities is financially outside the scope of the rehabilitation efforts now under way. Money for replacing them will have to be found elsewhere, officials said. A chilling reminder of how helpless humans are in the face of a major fire came from Tim Oliverius, the park’s fire-management officer. The Pony Fire reached the Wetherill Mesa developed area at about 6:30 p.m. on Aug. 4, a time of day when temperatures were starting to decline and relative humidity was rising, which caused the fire to shut down for the day. The fire had already run two miles during that day. Had the fire topped Wetherill Mesa at 2 p.m., when conditions were hotter and drier, Oliverius believes it could easily have run another two miles eastward across Long Mesa to the Chapin Mesa headquarters area. That would have threatened park housing, the research laboratory with the park’s collections, and the historic building complex, which includes the museum, park housing, ARAMARK’s operation at Spruce Tree Terrace and other structures. |

||||

|

Copyright © 2000 the Cortez Journal.

All rights reserved. |