|

Jan.

10, 2001

|

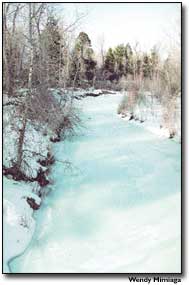

| THE LA PLATA RIVER, shown here south of Hesperus, is threatened by heavy irrigation use that dries up much of the small stream during summer months. Pockets of native fish habitat hang on and efforts are under way to save its natural habitat. |

By Jim Mimiaga

Journal Staff Writer

The natural health of two local rivers, the La Plata and San Miguel, suffers from heavy irrigation use and man-made alterations, according to a study released by Trout Unlimited this week.

The report, A Dry Legacy, the Challenge for Colorado’s Rivers, documents 10 case studies that show how streams and rivers are being harmed by overuse of a limited water supply.

The eight other rivers analyzed were the Conejos, South Arkansas, North Fork of the Gunnison, Colorado, Snowmass Creek, Bear Creek, South Boulder Creek and Cache la

Poudre.

Growth pressures are cited for the demise of rivers, as are antiquated “use-it-or-lose-it” water laws that discourage conservation. The ten examples are just a sampling of the 570 river waters identified by the Colorado Division of Wildlife that are limited by low and fluctuating stream flows.

“There is opportunity for the state to strike a balance that better combines our agricultural heritage along with our natural heritage, too,” said Dave Nickum, executive director of Colorado Trout Unlimited. “Right now the legal system in Colorado is counterproductive to wise use.”

|

Suggested strategies for

fighting low water levels

DENVER (AP) — In its report titled “A Dry Legacy: The Challenge for Colorado’s Rivers,” Colorado Trout Unlimited offers several strategies to combat low water levels in the state’s rivers and streams. Here are a few of the suggestions:

• Enforce Colorado’s law prohibiting the wasting of water.

•Support federal agencies’ power to protect — and even restore— certain streams both through permitting actions and through obtaining their own instream water rights in state water courts.

• Encourage agricultural and municipal conservation.

• Bolster the state’s existing instream-flow protection program with more strict enforcement, new filings, acquisition of senior water rights with state money and donations, and more money for monitoring.

The report also suggests borrowing strategies other western states with the same basic prior-appropriation water system use, including:

• Allow the water court to consider fishery, water-quality and endangered-species effects when issuing new or changed water rights, as happens in South Dakota, Oregon and Utah.

• Allow the water court to limit new appropriations out of systems that are already over-appropriated, as is done in Montana and the state of Washington.

• Allow anyone to convert an existing diversionary rights to an instream flow right, as is the case in California and four other western states.

• Allow private parties, including nonprofit organizations, to lease existing water rights for instream protections.

• Require water courts to condition new and changed water rights to incorporate conservation requirements as part of getting the new right.

Individuals can make a difference as well, according to the report:

• Conserve at home, both inside and in the yard.

• Participate in a local watershed group that does clean up or restoration.

• Become active in efforts to reform the water-law system. |

On the La Plata River, extensive diversions have dewatered large segments of the river downstream of Hesperus during summer months. Yet return flows have maintained some flow and allowed a rare native-fish community to survive in a five-mile river reach north of the New Mexico state line.

Roundtail chubs, blue-head suckers, speckled dace, flannel-suckers and mottled sculpin are doing relatively well in the stretch. But without protection, this remnant aquatic community may be lost as well, according to the study.

“The La Plata River is a classic example of why we need new tools to make sure what we have left remains,” said Melinda Kassen, Trout Unlimited’s project director.

Ironically, it is heavy diversion that is preserving the only native-fish habitat remaining on the La Plata. The structures dry up the river before its confluence with the San Juan River, effectively blocking non-native, predatory channel catfish from invading the upper reaches of the La Plata.

“But that isolation could be a genetic dead end, so it’s unclear if that remnant can hold on without more stable flows,” noted Mike Japhet, fishery biologist for the Colorado Division of Wildlife.

The La Plata River north of Hesperus is generally considered an intact river ecosystem.

On the San Miguel River, increasing demand for irrigation and municipal development in the town of Telluride has dried up long stretches between the headwaters of the river and its confluence with the Dolores River.

Fifteen miles of the San Miguel suffer from low or no flows because of large diversions on the Highline Canal and others during irrigation season.

Establishing minimum instream flows would help retain the San Miguel River’s lush riparian habitat and rare plant communities, the report states. To help ease the impacts of growth on sensitive environments, San Miguel County passed an open-space tax that has provided matching funds for lottery grants earmarked for purchasing conservation easements. Several easements have been established along the San Miguel River in the last several years.

Creative legal solutions that have worked in other states and keep rivers healthy in the midst of growth deserve consideration, according to the report.

The study points to Colorado law that punishes water-right owners if they do not want to use all of their allocation. Once unused water is let downstream, the owner risks being put on the abandoned list.

“The system does not encourage efficiency,” Nickum said. “The use-it-or-lose-it rule does not give incentive for someone who wants to use their water right for fish and wildlife protection, say, to improve a fishery stretch for anglers and commercial guides.”

Already, state Sen. Ken Gordon (D-Denver) plans to introduce legislation allowing private organizations to purchase water for the purpose of keeping it in the stream for natural values.

Retaining the ownership right to the water is critical, advocates of the bill say, because under current law, once water is “wasted” and sent downstream, the right is given up uncompensated to the state through the abandonment process.

“People should be able to retain that value if they feel it will be more beneficial to keep the water in the stream, say, during a drought year,” Nickum said. “It’s a fair option.”

Other strategies that have worked for many Rocky Mountain states are suggested in the report:

• In Oregon, irrigators are allowed to keep, use or sell 75 percent of the water they save through conservation so long as they return 25 percent to the stream.

• Rather than continue to allow limitless additional new water rights in over-appropriated watersheds, Colorado should consider closing some rivers to increased diversions.

• In Montana, although private individuals cannot own instream water rights, they can lease water for instream use for up to 30 years.

• Several states consider environmental and fishery effects before approving new or changed water rights.

Protecting native fish at a state level is preferable, Japhet said, because if ignored to a point of near extinction, a species could become threatened under the Endangered Species Act, which involves more-stringent federal protection with less local input.

In light of that, the CDOW has listed the roundtail chub on the La Plata as a species of special concern under state rules so that measures can be implemented to help it survive.

“We’ve learned through hard experience that it is better to prevent listing on the endangered list and having to go through the rigid, bureaucratic constraints of a federal recovery program,” Japhet said.

There is a pending application with the Colorado Water Conservation Board to establish a minimum, in-stream flow right in the La Plata River, he said.

Thanks to mitigation programs under the Animas La-Plata water project, nearly 6,000 acres of land along the lower La Plata is slated for acquisition by the Bureau of Reclamation pending funding, explained Kirk Lashmett, fish biologist with the bureau.

The agency must mitigate, through land purchase, wildlands and wetlands lost to the A-LP project now under way in nearby Ridges Basin.

The land, situated along a five-mile stretch near the Long Hollow confluence, will be improved to enhance its natural values.

So far the bureau has clear title to 1,000 acres. Purchase options have already been negotiated and signed with landowners for the remaining 5,000 acres. The total land deal is worth $6 million.

Negotiating conservation easements with property owners is also an option being sought for sensitive riparian areas in order to prevent river-dredging, channeling, and straightening, which can wipe out fish and wildlife habitat.

|