|

Sept 1, 2001

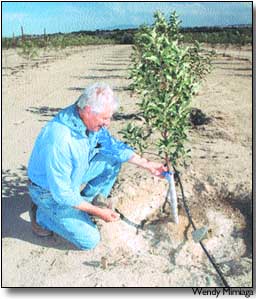

By Janelle Holden The slow drip of water may be annoying in the kitchen sink or the bathtub, but it’s the blood of life for desert fruit trees and specialty crops. Two demonstration projects in the region believe in spreading the gospel about slow drip-irrigation systems. In Shiprock, N.M., a demonstration project on Diné College land is watering fruit trees one drop at a time, bringing lush fruit to the arid climate without wasting precious water. And in Yellow Jacket, at the Colorado State University research station, a nearly 10-year drip-irrigation project is yielding another crop of healthy apples for this year’s harvest. The Shiprock project was the brainchild of CSU sociology professor John Wilkins-Wells, who lobbied the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for funds to build the system, which may encourage Navajo farmers to switch from traditional flood irrigation to the more efficient drip system. Seeing is believing, theorized Wilkins-Wells, who thus began a three-year project that became a labor of love for the numerous people who contributed to building the five-acre farm on Diné College land. Funding for the project came from both the Bureau of Reclamation and Diné College, which contributed $25,000 and $45,000 respectively. "The idea behind it is to get a high-dollar crop for small-acreage farms," explained Steve Miles, the owner of Rainmaker Sprinkler, who designed and installed the drip-irrigation system on the farm. "The main focus here (in Cortez) was that they had a limited source of water, they wanted to look at crop diversification, and we have a low-volume irrigation system, so let’s try it down there, and show them that it’s a possibility." Paul Gilon, the farm-project director for the past year, is quick to point out the number of hands soiled in the process of putting in fruit trees, fencing, and a drip-irrigation system over the past year.

Several of Gilon’s helpers hail from Cortez, including Miles. Extension agents Kenny Smith, Jan Sennhenn, and Dan Fernandez helped plant the trees. But Gilon also had local support. From Diné College volunteers to Shiprock High School Future Farmers of America students, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the "team" involved included 23 people. Before heading up the project, Gilon taught statistics and information systems in Long Beach at California State University for 30 years. It was during his search to find a college library for his 2,000 books that he found Diné College and eventually ended up teaching at educational centers across the Navajo reservation. Last December, Bernice Casaus, the dean of Diné College, asked Gilon to come back to Shiprock and take over the irrigation project, not because he had any background in agricultural but in his ability to organize and motivate people. Gilon’s belief in the project and his willingness to work without funding for the past few months has led to a remarkable collaboration. "This is going to be a local project where farmers can come and learn," explained Gilon with pride. Approximately 300 trees were planted in Shiprock this spring, including six varieties of apple trees and three varieties of peach trees. Miles and Fernandez, the Dove Creek extension agent, said that the growth and uniformity of the trees since is "jaw-dropping." "For the first year the growth is much more than expected," said Miles. "We’ve worked on this thing for two years, and put a lot of thought and effort, and a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into it. I think by next year we’ll have blooms." Eventually the project will include vegetable crops and several types of irrigation systems so that local farmers can investigate the benefits of each system. The Shiprock drip-irrigation system uses Navajo irrigation water, diverted into a canal, which is subsequently diverted into a pond on the farm that holds 100,000 gallons — enough water to irrigate the trees for one month. The pond allows the sediment in the water to settle out, and is eventually pumped into the drip tubing. Drip emitters are placed on the surface roots of the trees, so that the water has direct contact. Fernandez said that depending on the crop, drip irrigation can save up to 90 percent of the water needed for the fruit trees in the beginning, but the margin will eventually narrow to 30 or 40 percent when the trees grow to maturity. "The first five years it’s quite dramatic," explained Fernandez. "One irrigation cycle using siderolls on the same acreage uses more water than drip irrigation does in one month." The biggest drawback to drip irrigation is filtering out the silt, algae, and other muck that might come into the system with the water. Miles said that because of the pond and the self-cleaning filters installed in the Shiprock system, filtration hasn’t been much of a problem. He also said that the Dolores Water Conservancy District’s water is extremely clean, and the Yellow Jacket drip-irrigation system has not had a problem with the system clogging. Miles has been working on irrigation systems since 1977 and has 25 years of experience installing drip-irrigation systems. He says drip irrigation has really caught on among local farmers in the last six years. Two vineyards and one orchard in McElmo Canyon have installed the systems, and recently Miles installed a system for a raspberry farm in Durango. Miles says that drip irrigation is reasonably priced for the little maintenance required and amount of water saved. A drip emitter, on average, costs 40 cents a piece, and the tubing is normally $1 per tree. Most of the tubing has a life from seven to 10 years. Fertilizer and nutrients can also be injected into the irrigation system, and another benefit is weed control. Little water escapes to nourish the surrounding ground and the weed seeds in the soil. For more information on fruit crops and drip irrigation, call the Montezuma or Dolores County extension offices at 565-3123 and 677-2283 respectively. |

||||

|

Copyright © 2001 the Cortez Journal.

All rights reserved. |