|

Sept 4, 2001

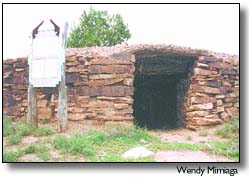

By Katharhynn Heidelberg Montezuma County can’t claim that George Washington or Abraham Lincoln once slept here. However, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, along with other famous outlaws, once did. Steve Lacy of Salt Lake City and Blanding thinks he knows exactly where. Lacy, author (with the late Joyce Warner) of Last of the Bandit Riders...Revisited, last week toured a site that many Cortezans believe to have been a hideout for Cassidy (born Robert Leroy Parker) and his cohorts. The site is a dugout, with timber supports and exterior masonry (the roof is reconstructed), located on private property on County Road K. Both local lore and documented evidence support it as a contender for the outlaws’ hideout. "I’m pretty excited," Lacy said of the dugout. "It adds to the documentation." The dwelling has a sweeping view of the surrounding area, including Sleeping Ute Mountain and Shiprock. Lacy explained that this would have been a logistic necessity for anyone who made his living by the gun. "This would have been pretty isolated for them," Lacy said. "You’re overlooking the valley and can see people coming for miles, but still have your back against something." He added that this sort of siting was "typical of hideouts" found in the now-legendary "Robbers’ Roost" area. "There’s a definite connection," tour conductor Cindy Bradley of the Cortez Cultural Center said of the structure. Sundance, whose real name was Henry Rodenbaugh, alias Longabaugh, had family who lived near County Roads 23 and L, Bradley said. Adding to this connection is local lore. Cortez barber Carl Armstrong certainly got an earful of it from the late Walter Longenbaugh, who regaled Armstrong with stories about his youth. When he was 12, Longenbaugh said, he used to carry milk, eggs and other supplies to Butch and Sundance, who lived in a "dugout cabin" outside of Cortez. "These were just stories to me," Armstrong said last week. "I’m not swearing by it." However, he said, "I always thought that was the cabin." Adding to the theory is documentary evidence, much of which is recounted in Lacy’s new book, a revision of the outlaw Matt Warner’s autobiography. Among the evidence is a picture of the Ute Mountain that looks as if it may have been taken from the site on Road K. Addressed to Warner, it is signed by "M.D. Morgan," thought to have been one of Cassidy’s many aliases. The back of the picture also includes references to a "ranch" and a cabin occupied by outlaw Tom McCarty (brother-in-law to Warner). Another photo, titled "View of one of the meadows on Ute Mountain," has an "X" drawn over the location of Cassidy’s cabin. Warner’s own words enforce the current theory: "At Cortez, we run (sic) into Tom McCarty...He had a cabin hideout eight miles out from Cortez in the foothills, and nothing would do but we go out there with our whole outfit and rest up a while and then go with Tom down to McElmo Gulch." It was in McElmo that an ill-fated horse race took place. By the time it was finished, their Indian competitor had been murdered, and the gang was high-tailing it out of the canyon. This sort of instability was part and parcel to the life of early criminals. Being an outlaw was "exciting, but a lonely life," Lacy said. "A lot of these outlaws were young Mormon boys," lured by the prospect of wealth and other pleasures. Like these pastimes, horse-racing was a man’s way of blowing off steam. Sometimes, it just didn’t turn out too well! Additional evidence indicating the cabin may have been a hideout is that Warner mentioned Indian ruins. A short way up the hill behind the cabin in question is an ongoing Anasazi excavation, and the whole area is littered with other Anasazi sites. The cabin itself is not built in the style the early Puebloan peoples used, but the nearby ruins would have provided ample building material for it. Although there is much to support the assertion that the cabin on Road K was occupied by Cassidy and other outlaws, Lacy and Bradley admit there are anomalies. The area was homesteaded by a family in the 1930s, and the cabin might simply have been one of that family’s outbuildings. Too, although there is archaeological evidence of site disruption at the Anasazi ruins, Bradley said the time frame for it is indeterminate. Occupation ceased around A.D. 1150. "It could have been other Anasazi, in the 1200s," who removed stones from the site, Bradley said. Or, it just might have been Butch after all. Neither the homestead from the ’30s nor the possibility of prehistoric pilfering preclude the possibility that Butch built — or at least used — the cabin, if one accepts Lacy’s theory that he died in 1943. For Lacy, there’s no doubt. "I feel really confident that this was Butch’s hideout," he said. |

||

|

Copyright © 2001 the Cortez Journal.

All rights reserved. |