Nov. 23, 1999

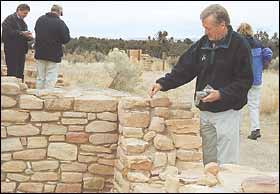

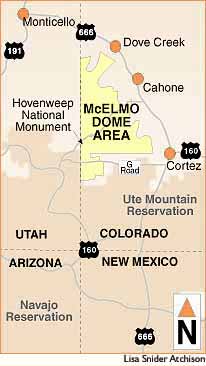

By Gail Binkly Saying there is a need to protect the entire landscape of Ancestral Puebloan sites west of Cortez rather than individual ruins, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt on Saturday reiterated his belief that a change in status is necessary for the 160,000-acre area. "It’s the landscape, stupid!" he said jokingly on a brief visit to Lowry Pueblo with several members of the national media, including the Los Angeles Times and New York Times, as well as representatives of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Bureau of Land Management. However, he said that public access for activities such as hiking would not change under his vision of management for the Anasazi Multiple Use Area of Critical Environmental Concern, which is administered by the BLM. "I can say that that will not change," Babbitt stated, "and what I will offer up is the existing national conservation areas and monuments." Twenty-five years ago, while governor of Arizona, he helped create the San Pedro National Conservation Area near Tucson, he said, "and I was down there last week and the community thinks it’s the best thing that ever happened. "There’s not a giant visitors’ center," he continued. "There’s protection for a landscape that extends the length of the San Pedro Valley, and you’re not going to find a single person in the valley who’s against it, because the access is open."

The management of the area has become "more intense" in terms of off-road vehicle use, littering and similar potentially destructive activities, he said, but the area, which is BLM-managed, is still open for public recreational uses. On his whirlwind visit Saturday, Babbitt also led his entourage to Sand Canyon, one of the sites he visited in May when he announced that he wanted greater protection for the Anasazi ruins dotting the landscape of western Montezuma County. Since that trip, a citizens’ subcommittee appointed by the BLM’s Southwest Resource Advisory Council has recommended stronger enforcement of existing laws and volunteer patrols rather than a change in status, which many locals oppose. The county commissioners, Colorado senators Wayne Allard and Ben Nighthorse Campbell and Rep. Scott McInnis have echoed that message, but Babbitt has remained adamant that the Anasazi ACEC needs to become either a national monument or a national conservation area, either of which would continue to be administered by the BLM. At Sand Canyon, Babbitt encountered Forrest and Carol Capps of the Mesa Verde Backcountry Horsemen and Chester Tozer, president of the Southwest Colorado Landowners Association, who voiced their opposition to further restrictions on the area. Babbitt referred to that encounter while at Lowry viewing an underground kiva where a mural has disappeared since the site was excavated and exposed to the air. "One of the issues driving our decisions is the need for protection of the landscape," he said. "You heard Chester saying, ‘There’s all these little piles of rock on the landscape you’re trying to protect.’ "That’s a traditional view, but the fact is that in a small site there may be more information than in a great big 200-room pueblo. The surprises come in many packages." Hovenweep National Monument, with its several small, scattered sites, is an example of "postage-stamp" preservation, Babbitt said, and much broader protection is needed on the rest of the county’s Ancestral Puebloan landscape. "Once it’s broken up, dug up or roaded over," the sites are damaged and the information that could be gained from them is contaminated or lost, he said. "Putting a road through Mockingbird Mesa is as destructive as excavating and losing these murals," he said. "How are we going to protect this and make it accessible without compromising it or destroying it? That’s the reason we need to talk about it." Dick Moe, president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, agreed and congratulated Babbitt for his persistence in pushing for new status for the ACEC. "It’s not an easy thing to do," Moe said, "but this is all our heritage." "You cannot tell the entire American story without preserving this," he said. "There’s more cultural history in this 150,000 acres than anywhere else in America. There’s more than 200,000 sites in this area and many are at risk." However, Victoria Atkins, an archaeologist with the Anasazi Heritage Center, said later that the figure is closer to 20,000 estimated sites than 200,000, based on concentrations at one of the few portions of the ACEC that has been formally surveyed. A site can constitute anything from a collection of potsherds to a check dam to an actual ruin, she said. Babbitt acknowledged that there is considerable opposition to national-monument or any other new designation for the ACEC, but noted there was also opposition when the Grand Canyon was first placed under protection of the National Park Service. He said the greatest danger to Montezuma County’s Ancestral Puebloan ruins is deliberate vandalism such as pothunting, as well as "the fragmentation and destruction that comes from uncontrolled vehicle use." "Big-time vandalism can be controlled, I think, with a moderate amount of resources," Babbitt said, stating that volunteers are very important in monitoring and protecting ruins. "You don’t excavate a site like this over lunchtime," he stated. In some resource-rich areas in Arizona, he said, voluntary aerial surveillance provides protection. "Plane owners who are also archaeologists fly over on their way from city to city," he said. "That’s enormously effective." Babbitt noted that there had been discussions of creating an Anasazi National Monument in the county in the late 1980s and early ‘90s and that Campbell had spoken favorably of the idea. "This wasn’t some idea that I brought in in a bell jar from Washington," he said. Babbitt said his next step will be to meet with members of the Colorado congressional delegation after Thanksgiving. "I have no schedule in my back pocket except that I want to get this to a decision by the end of next year," he said. |

|||

|