|

Jan. 18, 2001

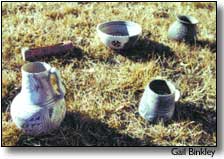

By Gail Binkly Journal Managing Editor In seeking to preserve history, a Montezuma County landowner is making a little history of his own. In December, after about a year of work, owner Don Dove and the Montezuma Land Conservancy finalized a conservation easement on Doveís 110-acre, ruins-rich tract south of Cortez near Mitchell Springs. Itís the first such easement in Colorado designed specifically to protect archaeological resources. "There have been others around the country, but Iíve not heard of any others around the West," said Kevin Essington, executive director of the Montezuma Land Conservancy, a local non-profit organization that helps landowners with voluntary land conservation. "But all I know is this is the first one in Colorado." The easement includes penalties for excavating the Ancestral Puebloan resources on Doveís property without following proper procedures. "Itís not uncommon for someone to do a conservation easement who has some archaeological resources on their place, but itís often dealt with as sort of an afterthought," Essington said. "But we went into this project knowing right away that was the primary conservation value we wanted to protect." Essington said he approached the Archaeological Conservancy, an Albuquerque-based non-profit group, about the easement, but its directors said they didnít do easements, only outright purchases of valuable sites. "They didnít have a copy of an archaeological easement that we could go off of," Essington said, "so we really had to go from scratch. Itís taken us about a year to get this all together." Doveís property is believed to be the longest continuously occupied Ancestral Puebloan site in the area. It contains a number of archaeological features, many still undiscovered. "We really donít know how many," said Dove. "At one time we estimated there were 30, but thereís a lot of stuff we simply canít see." The features include pueblos ó some small, some containing 20 or 30 rooms; a great kiva; and an unusual tri-wall feature. The latter, Dove explained, is appended to the end of one of the larger pueblos. It consists of three parallel, horseshoe-shaped stone walls, the inner one apparently belonging to a raised platform. No doorway or entrance is evident, he said. "Itís not circular, like most tri-walls, and theyíre fairly rare," Dove said. "Its use is really unknown. Often they (the Puebloans) attached a ceremonial significance to the structure. One expert think itís a solstice feature, but thatís speculation." The ruins on his land date from around 805 A.D., possibly earlier, to the mid-1200s, when the site was abandoned, Dove said. "We donít know if there was any hiatus of occupancy at all, but if so, it was short-lived," he said. Dove, a retired electrical engineer who has a masterís degree in archaeology, team-teaches classes every summer on his property for students from Glendale Community College in Arizona. The students do careful excavations and report on the results. "We simply sample," Dove explained. "Itís not our intent to fully excavate anything. We want to find out the time frame (of occupancy) and the type of architecture, and learn about social groups." Dove purchased the property, which was once part of a 160-acre tract, in 1988 from the granddaughter of the person that had homesteaded it. He immediately began thinking about preserving its ancient ruins, but didnít take action until about a year ago. He and Essington included some typical measures in the conservation easement, such as prohibiting the land from being subdivided and banning any more dwellings on it (those there can be replaced if necessary). But the easement also contains the requirement that any excavations done on the property be conducted with a permit from Coloradoís State Historic Preservation Office, which issues permits for excavation projects on state lands. "They agreed to review and approve permits on that easement, which Don already does for his field school," Essington said. "They said, ĎWeíd be happy to do that for you.í "The hammer we put into this easement is we put in some penalties for anyone that disturbs the sites by bulldozing, pot-hunting ó the more heinous acts." The penalties call for fines of up to twice the research value or the commercial value of the artifacts, Essington said, and apply to anyone, even future owners of the land. "We thought, ĎWe build this easement and say, "Donít excavate out there" ó so what?í" he said. "What if somebody did it?" Once plundered, archaeological resources canít be restored, he pointed out. "So we put in the penalties." The easement will be held by the La Plata Open Space Conservancy, which holds most of the easements developed through the Montezuma Land Conservancy. The State Historical Fund provided a grant to research and implement the easement because private, voluntary incentives for landowners to conserve archaeology are non-existent, Essington said. This is the fourth conservation easement completed by the Montezuma Land Conservancy. Anyone interested in such easements can contact the conservancy at 565-1664. |

||

|

Copyright © 2001 the Cortez Journal.

All rights reserved. |